How Do WNBA Players Age? (Part I)

An analysis of player aging curves and productivity changes throughout WNBA careers

October 2025

Knowing how WNBA players age is crucial to better understanding their development. If a player is underperforming, should coaches and management practice patience since that player may have years of improvement ahead of them? If so, approximately how much improvement should they expect? Or has the developmental window closed and regression likely imminent?

Furthermore, if a player's contract terminates should she be re-signed? If so, for how long? Or would it make sense to sign or draft a replacement who is younger and has a learning curve but also their peak years ahead of them? In these next couple of articles I'll explain how I examined aging of WNBA players, what my analysis shows, and how different players and play styles may age differently.

Methodology

Since win shares (WS) seem to correlate best with team wins (see previous Win Contribution post), I tracked how WS changes for each player from one age to the next. Below are further notes about how I constructed these age curves:

- I followed a similar methodology to the one delineated on hockey-graphs.com.

- I used WNBA player WS data from 1997-2025 from basketballreference.com.

- I scaled a player's WS each season to a 40-game season so we could compare year-to-year player productivity despite varying season lengths. For instance, when there were only 22 games played in 2020, I multiplied a player's WS by 40/22 to account for the shortened year. Since 2025 had 44 games, I multiplied each player's WS by 40/44.

- A player's age for their season was determined by how old they were on July 1st. For instance, Nneka Ogwumike turned 35 on July 2nd, 2025, so she is marked as a 34-year-old for the 2025 WNBA season.

- Only players with back-to-back season were included in the delta WS analysis. Therefore, if a player played in 2022, 2024, and 2025 only the 2024-2025 two-year stretch was included in the delta WS method and the change from 2022-2024 was omitted.

- To control for playing time and pace, I also examined WS per 100 possessions. For this analysis, players who had less than 200 minutes played were removed.

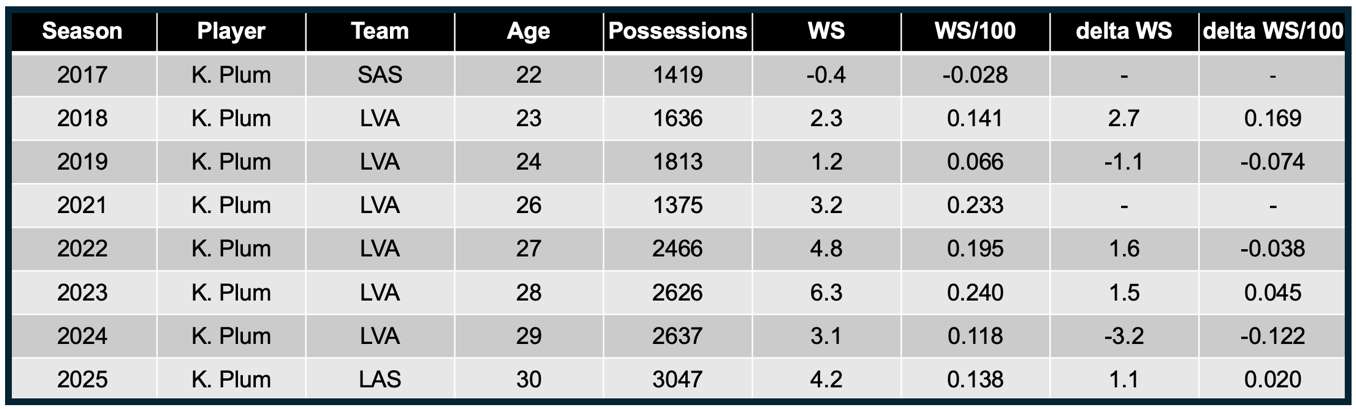

- Below is an example of how I calculated change in WS for Kelsey Plum. Notice how her 22 and 26 years are omitted from the analysis due to her not playing in the preceding year.

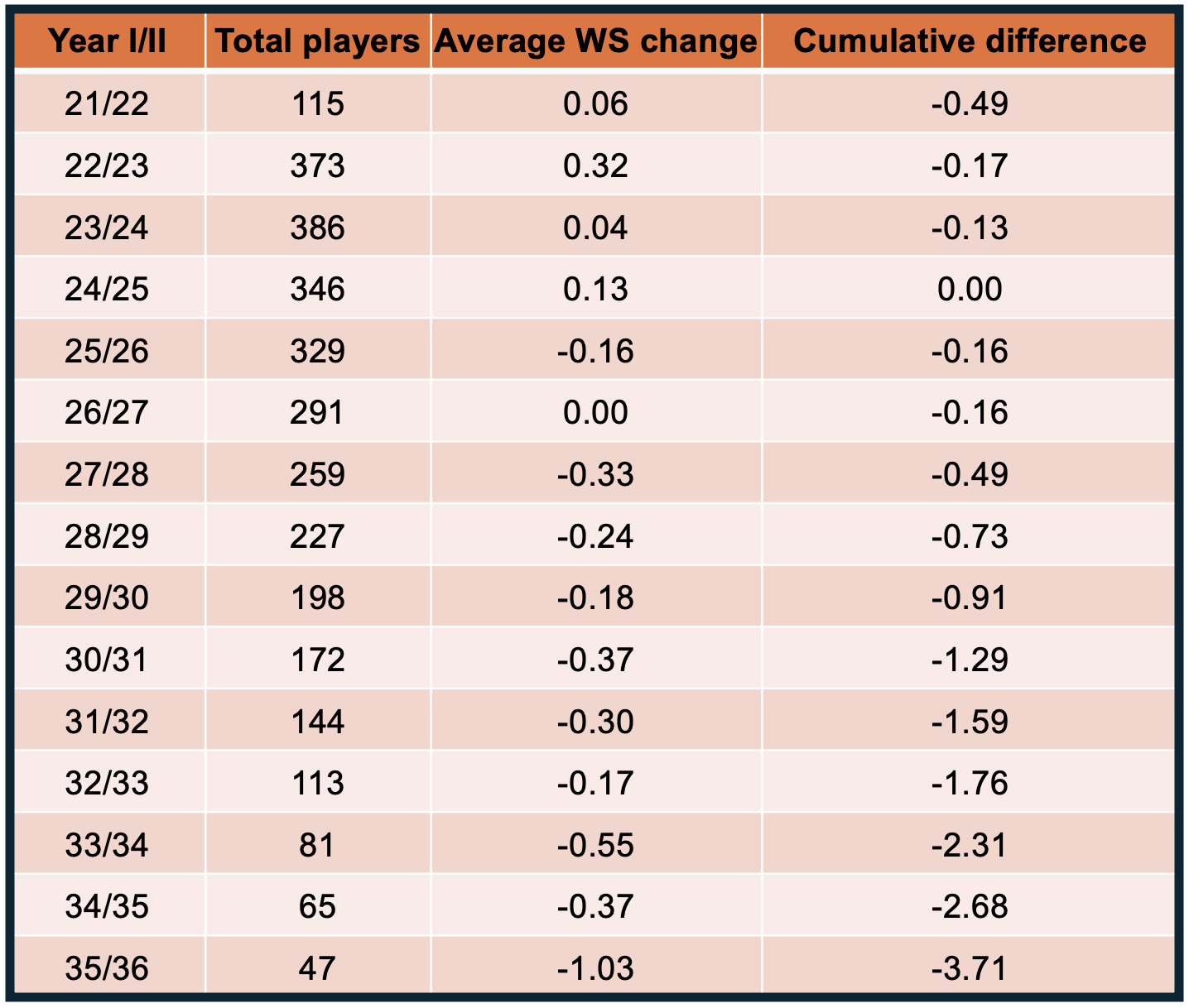

After calculating delta WS (as shown above) for each player, I then averaged all the WS changes for each age bin (21-22, 22-23, 23-24, etc.). I summed the average changes into cumulative change and adjusted the peak to 0 to best visualize the aging curve.

Results

Below is a table and graph of the cumulative difference in WS for each age:

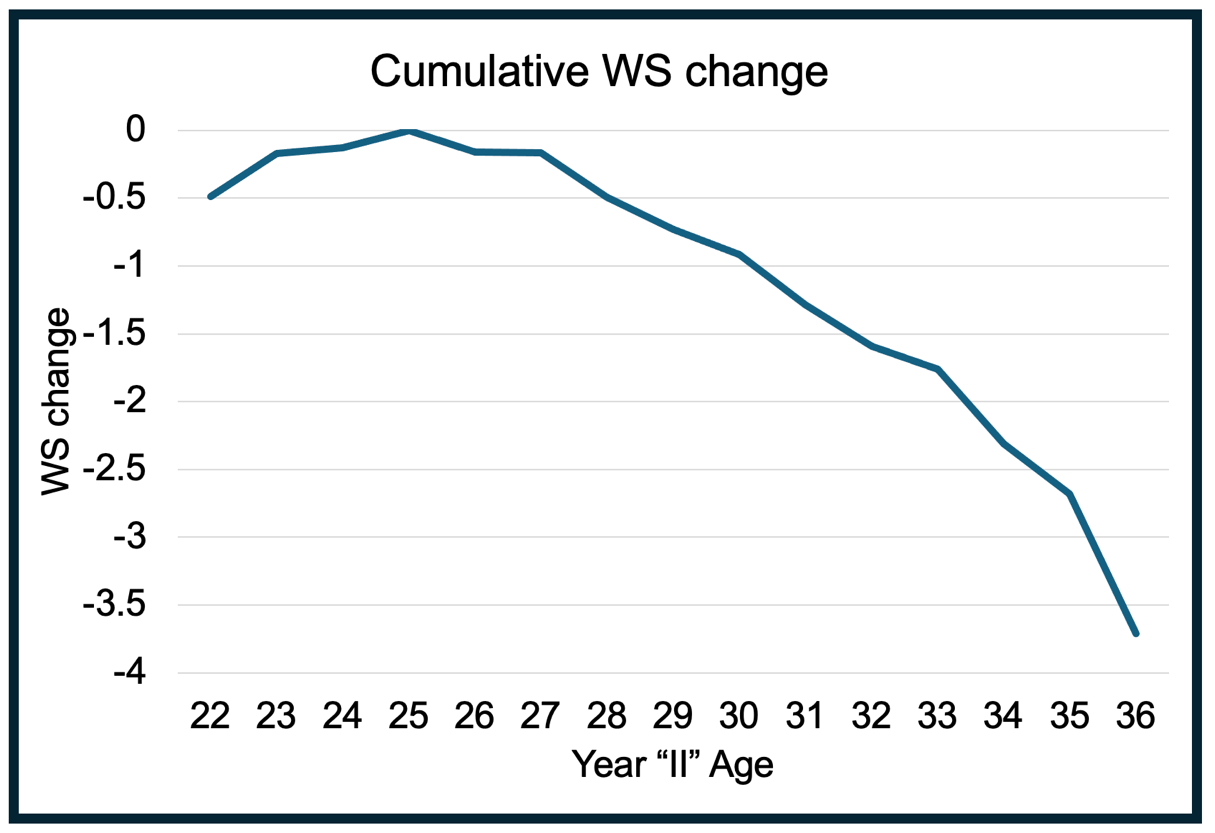

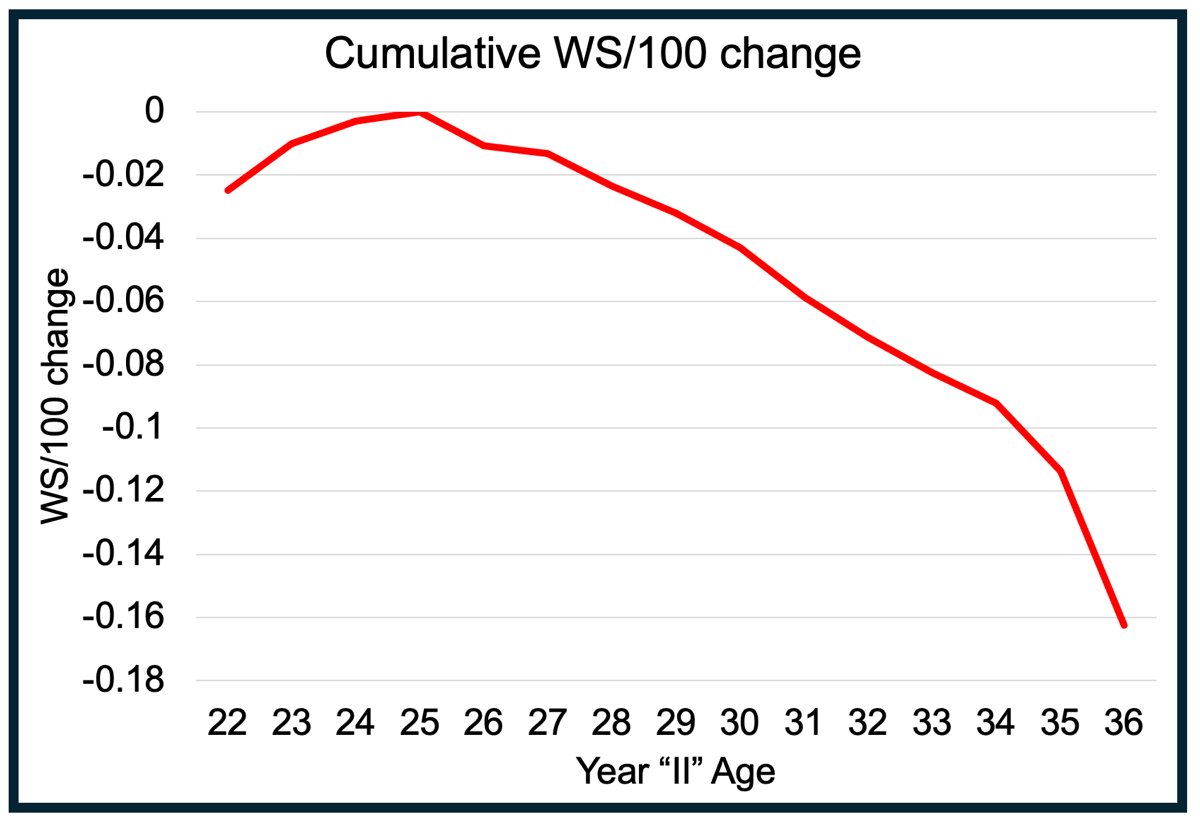

And below is how WS/100 possessions change with age:

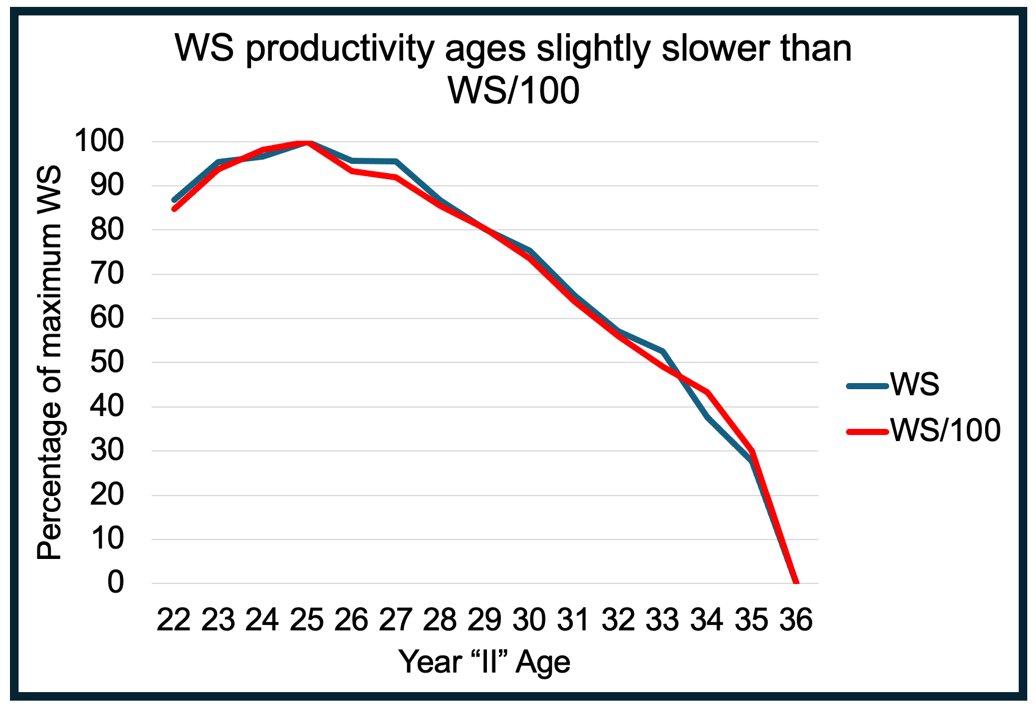

If we overlay these plots and change the axis to percentiles of each of their maximums, we see that they mostly overlap suggesting that normalizing for possessions does not significantly impact our conclusions about WNBA aging.

However, it does look like the WS curve declines slightly less in ages 26-28 than the WS/100 curve. This suggests that 26-28 year-old players may start declining quicker on a per possession basis than raw WS suggests, but maybe increased playing time from their coach increases their gross productivity and makes their decline appear slower.

One final note about methodology is that we did not factor in survivorship bias which would be important to consider in future analyses. I would hypothesize that factoring in survivorship bias would flatten this aging curve slightly, as the survivors may have been lucky in their contract year and thus gotten an extra contract out of it. If so, they most likely regressed in that extra year and thus showed poor production which would steepen the aging curve. Meanwhile, the non-survivors who had an unlucky year and could not secure another contract (and therefore are not included in this analysis) may have positively regressed and showed better production in their non-existent year, ergo flattening the aging curve. This hypothesis needs to be tested.

Conclusions

As you can see from the graphs, WNBA players on average are most productive from the ages of 23-27 and start showing consistent decline in both raw and per possession productivity starting at the age of 28. From when a WNBA player gets drafted at 22 to when they tend to hit their most productive year at 25, management can expect that player to improve their WS total by 0.5 on average over a 40-game season or 0.55 wins in a 44-game season. Conversely, from their peak at age 25 to 28, a player will on average lose a half WS over a 40-game season and then another 0.8 WS over the next three year stretch from 28 to 31 years of age. From there it gets even steeper with a player on average losing over a full WS from 31 to 34.

These may seem like minor changes but in 5 of the past 6 years in the WNBA, a team missed the playoffs by one game. Further, when one considers a team's rotation is 8-10 players, these aging effects can multiply to significantly impact a team's place in the standings. Thus, understanding when and to what extent a WNBA player ages can better inform a front office and coaching staff how best to plan and manage their roster and distribute minutes to yield the most wins for their team.

Remember these are simply averages and not consistent rules for every player. Each player has distinct habits, biology, training, coaching, and play styles which will affect their aging. Additionally, there is randomness included in all of this. In part II we'll study how different position types may age differently while part III will examine how different play styles age.

This is Part I of a series on WNBA player aging: